What Are Alpha and Beta in Investing (and How to Calculate Them)

In the investing world, we often hear about Alpha and Beta—two foundational indicators to evaluate performance and risk for portfolios, funds, and ETFs. These concepts come from the standard reference model, the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), and are used by both retail investors and professionals to understand how an investment behaves relative to the market. In this article—written in an accessible style but with technical depth—we’ll see exactly what Alpha and Beta indicate, how to compute them quantitatively, and provide practical examples using real data from U.S. sector ETFs to illustrate their use. The goal is to help investors (especially passive ETF investors) better grasp these concepts and extract useful insights for their decisions.

Alpha and Beta at a glance: why they matter

Alpha and Beta are two sides of the same coin. In short:

- Beta measures the volatility and systematic risk of an investment relative to the reference market (e.g., the S&P 500). It tells us how much the security or fund follows market moves.

- Alpha measures an investment’s excess return relative to what would be expected based on its Beta. It indicates whether the return earned is above (or below) what is justified by the market risk taken.

In other words, Beta tells us how correlated and risky an investment is relative to the market, while Alpha tells us how much it returns in excess of the market, net of the risk taken. These indicators are crucial for evaluating funds and ETFs: for example, a passive fund replicating an index will have a Beta close to 1 and Alpha around zero (it faithfully tracks the market), whereas an active manager will seek positive Alpha (to beat the market) possibly assuming a certain Beta (market exposure).

Beta: what it is and how it works

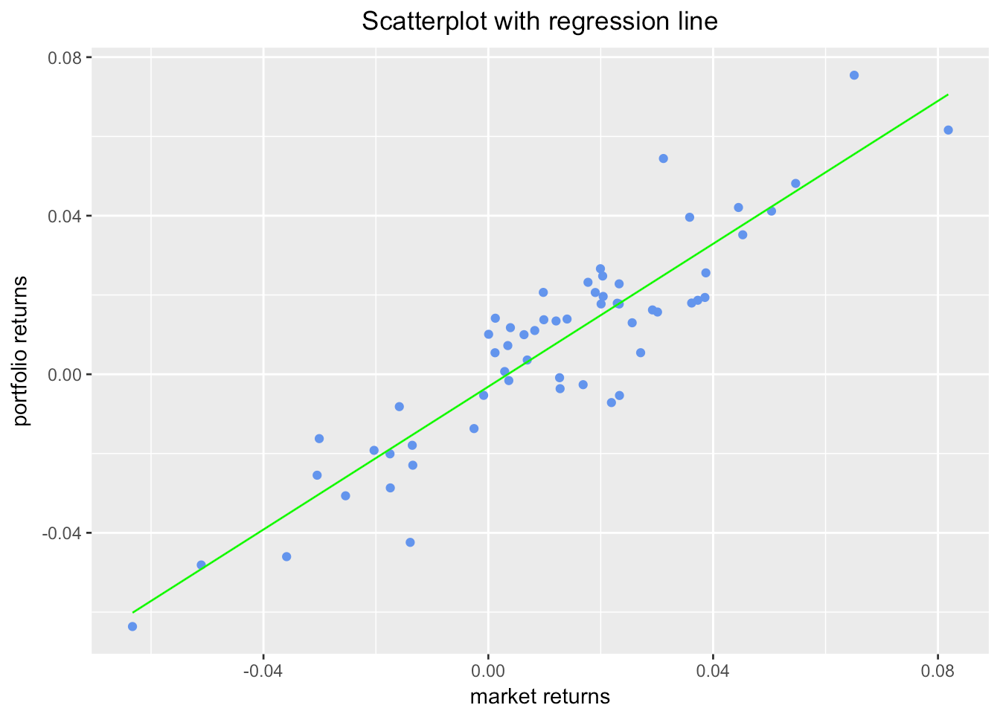

Beta (\beta) is a coefficient that defines the measure of systematic risk of a financial asset or portfolio. Technically, the Beta of an investment relative to a market index is computed as:

where are the returns of investment and are the returns of the market (benchmark index). Put simply, expresses how much the security’s moves follow (or amplify, or dampen) the moves of the reference market. The practical computation of Beta requires:

- Historical return data—e.g., collect monthly returns of a security or ETF and the corresponding market index for a given period (say, 3 years).

- Covariance and variance—compute the covariance between the security’s returns and the market’s returns, and the variance of the market’s returns.

- Covariance/variance ratio—dividing covariance by market variance yields Beta. This is mathematically equivalent to the slope of a linear regression of the security’s returns (dependent variable) on the market’s returns (independent variable).

Interpreting Beta

- : the investment moves, on average, in line with the market. If the market gains +1%, the security ~+1%; if it drops −1%, the security ~−1%. A Beta of 1 signals volatility similar to the benchmark.

- : the investment is more volatile than the market. It tends to amplify moves (e.g., ).

- : the investment is less volatile than the market (same direction, attenuated).

- : the investment shows no correlation with the market (independent moves).

- : the investment moves in the opposite direction to the market (negative correlation).

Beta thus measures systematic risk: the risk tied to market-wide moves that cannot be eliminated via diversification. By definition, the market (benchmark) has . Knowing a security’s or fund’s Beta helps assess how exposed that product is to market swings.

Conceptual example: imagine a fund with . If the market gains +10% in a year, we expect (on average) the fund to gain ~+15% thanks to its high beta. If, however, it earns only +12% or, conversely, +18%, the difference relative to what was expected is Alpha—which we cover now.

Alpha: what it is and what it shows

Alpha (\alpha) represents an investment’s ability to generate additional return independent of the market. In practical terms, Alpha is the extra (positive or negative) return that a manager or security earns relative to its benchmark after accounting for market risk (Beta).

In an actively managed fund, Alpha measures the value added (or destroyed) by the manager: an indicates the fund beat the market; an indicates underperformance. For passive (indexed) ETFs, one expects .

Methodologically, Alpha is the intercept in a linear regression of the investment’s returns on the market’s returns. Using CAPM (in excess over the risk-free rate), the baseline relation is:

Rearranging yields Jensen’s Alpha for a portfolio :

Interpreting Alpha

- : return equal to what is expected given Beta (neither out- nor under-performance).

- : return above what CAPM predicts (market-independent value added).

- : return below what is due for the risk taken (underperformance).

Together with Beta, Alpha is among the primary indicators for risk-adjusted performance (alongside standard deviation, Sharpe, R², Sortino/Information, etc.).

Passive vs active management: the role of Alpha and Beta

In passive ETF investing, the core concept is market Beta: buying an index ETF means buying Beta, i.e., the market’s performance (minus costs). Expected Alpha is near zero. In active management, the goal is to produce positive Alpha via security selection, sector tilts, and market timing. However, consistently beating the market is difficult; over long horizons only a minority of active funds deliver persistent positive Alpha after costs.

Practical examples: computing Alpha and Beta for sector ETFs

Consider two U.S. sector ETFs: Technology (e.g., XLK) and Utilities (e.g., XLU), with the broad S&P 500 as benchmark. These sectors have very different risk/return profiles: tech is more volatile with strong returns over the last decade; utilities are more defensive.

(Conceptual) figure

Technology sector Beta vs S&P 500

The Technology sector ETF (ticker: XLK) in recent years has exhibited volatility well above the market. Calculating Beta on a historical basis (for example using monthly returns over the last 5–10 years), one finds that the Beta of XLK relative to the S&P 500 is slightly above 1, indicating amplified sensitivity. Indeed, the standard deviation of XLK’s returns is roughly 27% per year, versus ~19% for the S&P 500[1], with a high correlation to the market (given the equity nature, correlation near 1 is not far off). This leads the Tech sector Beta to be around 1.1–1.2 (about 10–20% more volatile than the market). A Beta >1 was predictable: tech companies tend to be more subject to economic cycles and fluctuations (think of the declines during the dot-com bust or the rapid climbs in recent years), so they have higher systematic risk. For a concrete calculation, we use a 10-year horizon. Between 2015 and 2025, the XLK ETF recorded a compounded average annual return of about +23.3%, compared with ~+15.3% per year for the S&P 500[2]. Assuming an average risk-free rate negligible in those years (it was very low, around 0–2%), we can estimate Beta and Alpha:

- Beta (XLK) – suppose β = 1.2 over 10 years (consistent with the higher observed volatility of 27% vs 19% and high correlation).

- Expected return according to CAPM – Given β=1.2, if the market returned +15.3%, the “expected” return for XLK would be: R_f + 1.2 × (15.3% − R_f). Even assuming R_f ≈ 0%, this yields an expected ≈ 18.4%.

- Actual return of XLK – ~23.3% per year.

Utilities sector Beta vs S&P 500

We now turn to the Utilities sector ETF (ticker: XLU), which includes electricity, gas, water companies, etc. Utilities are considered defensive: relatively stable demand, high dividends, lower sensitivity to economic cycles. We therefore expect a Beta below 1. Indeed, historically the Beta of XLU hovers around 0.7 relative to the S&P 500[3]. This means that if the market rises or falls by 10%, the utilities sector on average rises/falls by about 7%. Data confirm lower volatility: for example, the daily standard deviation of XLU is around 16–17%, significantly below that of the S&P 500 (~19%)[4], with moderate correlation. Looking again at the 10 years 2015–2025, XLU achieved a compounded average annual return of about +10.9%, compared with +15.3% for the S&P 500[5][6]. We estimate:

- Beta (XLU) – about β = 0.7 (as observed historically).

- Expected return according to CAPM – With β=0.7 and the market at +15.3% (taking the risk-free rate as negligible), CAPM would give an expected return ≈ 0% + 0.7 × 15.3% = 10.7% per year. (If we assumed R_f = 2%, it would be 2% + 0.7 × (15.3% − 2%) = 2% + 0.7 × 13.3% = 11.3%. The idea changes little.)

- Actual return of XLU – ~10.9% per year.

Comparison and considerations

From the example, it is clear that Beta and Alpha together paint the full picture: XLK (Tech) had Beta > 1 and produced a substantial positive Alpha (it outperformed beyond market risk), while XLU (Utilities) had Beta < 1 and produced Alpha ~0 or slightly negative (it returned less than the market, but proportionally to the lower risk taken). For a passive ETF investor, these indicators help understand the nature of one’s portfolio: if one holds many “aggressive” sectors with high Betas, one can expect more volatility and potentially extra return in bull markets (but risk of underperformance in bear markets); defensive sectors will provide stability (low Betas) but will unlikely beat the market in prolonged rallies. It is important to note that Alpha, being a historical measure, is not guaranteed in the future: the fact that tech had ~5% per year of Alpha over the last 10 years does not mean it will maintain that in the next 10 (it could decline if the sector slows or if other sectors catch up). Similarly, a past negative Alpha does not condemn a sector forever—but often reflects structural dynamics (e.g., difficulties in beating the market for actively managed funds, or mature sectors that grow less than average). Finally, recall that Alpha and Beta are calculated relative to a specific benchmark: choosing the right benchmark is crucial. In our example, we used the S&P 500 for both sector ETFs; this is fine for a general comparison, but sometimes to truly assess a manager’s skill it is better to use a more targeted benchmark. For example, a technology sector fund should be compared to a tech index (its Alpha versus S&P 500 also reflects sector effects); however, from an asset allocator’s perspective, comparing to the broad market helps understand how the sector contributes to the portfolio’s overall performance. The key is consistency: Beta and Alpha make sense only relative to the same reference index.

Conclusion

Alpha and Beta are two key financial parameters: Beta quantifies an investment’s exposure to market risk, while Alpha measures its ability to generate extra return relative to the market. For passive ETF investors, Beta and Alpha help understand how to combine various products to build the desired risk/return profile— knowing that most of the return will come from market Beta, while generating consistent Alpha is difficult and rare. A deep understanding of these concepts helps better evaluate investment performance: for example, distinguishing whether a fund is beating the market because of Beta (perhaps because it is riskier) or because of true Alpha (manager skill, stock selection, etc.). In a field where people often search for “miraculous active strategies,” Alpha and Beta refocus attention on the fundamentals: how much of the result is explained by market movements, and how much is true value added? The vast majority of returns can be traced back to Beta (i.e., market factors); genuine Alpha is rare and valuable—hence the name “alpha,” the first letter of the Greek alphabet, as if indicating something special. It’s no coincidence that the financial jargon speaks of “alpha hunting.” But as investors, one must be aware that this hunt entails costs and risks, and that often a good strategy is to secure market Beta efficiently (for example with low-cost ETFs) and not chase elusive Alpha at all costs.

In conclusion, Alpha and Beta are conceptual tools that help us navigate the waters of financial markets: knowing them and being able to calculate them gives us an edge in understanding why our investments are doing well or poorly, and in making informed decisions for the future. Whether you choose the simplicity of a passive portfolio or venture into active strategies in search of Alpha, keeping an eye on these indicators will help you stay anchored to risk-return fundamentals.

Helpful sources

- Investopedia — Alpha and Beta for Beginners

- Moneyfarm — Beta and Alpha: Meaning in Finance and Investing

- Corporate Finance Institute — Alpha – How to Calculate and Use Alpha

- PortfoliosLab — ETF Comparison Tool (historical data XLK, XLU vs SPY): XLK vs SPY • XLU vs SPY

- Institute of Business & Finance — S&P 500 Sectors: Beta, Correlation, R² & Weightings: icfs.com